CONECTO.MX

In Queretaro, in a cultural climate of machismo and extreme poverty, the Sierra Gorda Environmental Group is helping local women find their voice by managing profitable projects.

When María Aguas told him that no, she didn’t want to be with him, he came back to her with an ultimatum: “If you don’t marry me, I’ll kill you”. He was 40 and already a widower. She was 14 and was looking for a way out of extreme poverty.

Four decades have gone by since then but María tells the story calmly as she sits facing the bar of her simple restaurant on the side of the highway. With her cute white hat, navy blue vest and ready smile, Doña Mary – as she is known these days – looks very much the part of the cheerful and proud great-grandmother she says she is.

“He was one of those old-fashioned men who would say ‘You’re going to do what I tell you’; these kind of men no longer exist. No, really, in those days men really humiliated their wives. They would beat them.

”I did have that to thank him for: he didn’t beat me, he didn’t hit me. I followed him around town so he could do the shopping: I didn’t know how to shop,” Doña Mary recalls in the interview. She makes it clear that to break free from suffering you have to work hard, which is why she wakes up every day at five in the morning to prepare the casserole that she sells at her inn on the side of the San Juan del Río-Xilitla federal highway

Unfortunately, the bad experience this mother of eight has already overcome is still very much a reality for many women living in the communities of Queretaro´s Sierra Gorda – a place where the prevailing mentality is that a woman shouldn’t leave her house let alone work, according to the testimonies Conecto.mx gathered from the habitants during a visit to the hills and plains of the Sierra.

There, it is common to find women who have more than eight children, something that was a demographic trend in the state 45 years ago.

Its still women who lag behind in terms of education, although it is true that the number of people who cannot read or write fell between 1960 and 2005 and that the gap between the two sexes is shrinking, according to the Queretaro Women’s Institute (IQM).0}

In 2005, in Pinal de Amoles – one of the five municipalities comprising the Sierra Gorda Biosphere Reserve -, 23.4 percent of women over the age of 15 were illiterate, as opposed to 18.5 of their male counterparts. In contrast, in the capital of Querétaro, only 3 percent of men over the age of 15 were illiterate, as opposed to 5.5 percent of their female counterparts, according to the census information referred to by the IQM. Statewide, the average level of male illiteracy was 6.3 percent and 10 percent for women.

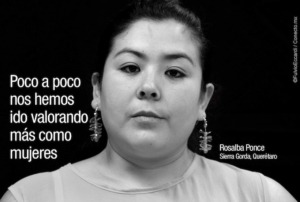

Rosalba Ponce, Nature Motifs Embroidery Workshop

For Rosalba Ponce, from La Colgada community in the Pinal de Amoles area, there is only one type of man: the chauvinist. When Conecto.mx asks if the women’s participation in the Embroidery Workshop has had any effect on the dynamics with their partners, this 23-year-old woman, with her gaze set on the camera lens and a firm, unwavering voice replies that it has.

“It has been more than difficult. Some of the womens’ husbands are like all men: they are chauvinists. They say ‘I’m supporting you so you stay in the kitchen; if I give you money, where are you going? What you want is to be out in the streets but I give you money and a woman’s place is in the kitchen.

“It has been really difficult, fighting against chauvinist people as well as against ourselves,” Rosalba explains, speaking as much for her peers as for herself.

The Embroidery Workshop, founded in 2004, now has 30 members. It started off as a competition between the communities in the region, in which La Colgada won first place. In the beginning, they worked in public spaces like shops, the church or schools until, eventually, with the help of some institutions, they built their own facilities for the workshop. They meet in the workshop to socialize and share their needlework, which captures the nature that surrounds them: birds such as the hummingbird, the trogon or flycatcher; flowers such as daisies, cacti such as walking-stick chollas or trees such as holm oaks, to name but a few.

The women who run it are the owners of the microenterprise, which means that the money that each one makes goes directly into her pocket. “I don’t earn very much, but there is no work here and sometimes with my wages we can survive for a week or a month when he doesn’t go to work. Even though it’s not much, we make ends meet,” Rosalba tells us, just before admitting that she is gradually showing her husband that he should value her both as a person and as a woman.

The workshop, as well as being a business which improves the quality of life and increases the self-esteem of its members, is a project that raises awareness about the diversity of the flora and fauna of the surrounding area – an important task when you take into account the fact that the Sierra Gorda in a protected natural area that is home to endangered species such as the jaguar and the military macaw.

“We are like an army of ants because each woman does her own job. Some of them cut and then they paint and then, from there, the material goes to the person who puts on the thread, each woman embroiders what she can, and then from there they are handed over to be ironed, packed and distributed to shops, fairs or craft centers,” explains Rosalba, boasting that her products have been shipped as far away as Spain and been bought by the ex-governor’s wife.

María Soledad Velázquez, Fonda Doña Chole

As she adds two cups of coffee to the boiling water, María Soledad Velázquez, or doña Chole as she’s known, declares: the only viable future for the Queretaro´s Sierra Gorda is tourism. “We have to bet on tourism. We don’t have factories, we don’t have companies, we don’t have anything for the population to make a living from,” explains doña Chole, who directly benefits every time a diner comes to be eatery on the side of federal highway 69.

Despite having more than 35 years’ experience in the food business, for the past five years, she has belonged to the Ruta del Sabor, the Taste Route, a network of local entrepreneurs supported by the Sierra Gorda Environmental Group, who works to better peoples’ living conditions while being socially and environmentally responsible. Doña Chole tells us that she raised her six children on her own. he mamaged

“I didn’t study, love. I made it to fourth grade of primary school, well actually I made it to third grade really, because I didn’t finish fourth grade. My sons are already grown-up: two are architects, and I have two daughters, one is an accountant and the other is an accountant’s assistant. The other two didn’t want to study, love, but they are very hardworkers. One has a blacksmiths’ workshop and the other one is going to the United States; they all turned out to be such hard workers.”

Graciela Vega Hernández, Cuatro Palos Cabins

The face of Graciela Vega Hernández looks overwhelmed with sadness when she is asked about her personal life. “There were times when he would hit me [my husband]. I put up with abuse for 6 years. He didn’t like me to talk to anybody, like now that I’m talking to you, the fact that we are talking would annoy him, I don’t know why,” Graciela recalls while looking off to the side. Her husband didn’t like her to dress up, or that she planned her pregnancy, or that she went out to the shops or to her parents’ house.

“Sometimes I went out heavily pregnant and I would say to him: ‘who is going to be interested in me? What, with me already being pregnant and with you’, but he didn’t like it.” Despite everything, life goes on and at the moment, Graciela forms part of the group of women who manage and own the Cuatro Palos cabins.

In one of the most extraordinary meeting points in the Sierra Gorda, seven women built the cabins with their bare hands, using bio construction with mud, a building technique that uses materials with low environmental impact, extracted using simple, low-cost processes.

The cabins command a spectacular view of the Cerro de la Media Luna, showing the transition from the temperate forest ecosystem in the high parts of the mountain range to the arid xerophytic scrub vegetation of the semi-desert.

Graciela is the secretary of the organizing committee, which means that now her 10-year-old daughter sees how her mother, now separated, goes in and out of the house to take food to the tourists staying in the cabins.

Isidra and Ma. Flora, the group’s president and treasurer respectively, laugh at the thought of their husbands trying to get their hands on their business and make it clear that the cabins and their dividends belong to nobody but the group of seven women.

“Well, he used to tell me to hand it over because he didn’t want me to come here. But it was so hard for me to make the cabins that there was no way I was going to hand them over to someone else. Come rain or come shine, here we were, working in the mud. I’m not leaving,” says Ma. Flora, letting out a chuckle.